|

|

Abstract

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is an uncommon acute

pustular eruption most often triggered by systemic drugs. We report a 68-years-old

female patient who developed AGEP after the intake of fenofibrate. To our

knowledge, this is the first report of this association in medical literature.

Therefore, fenofibrate should be added to the list of AGEP-causing agents.

Introduction

In 1980 Beylot et al. [1] introduced

the term pustuloses exanthemátiques aiguës généralisées (acute

generalized exanthematous pustulosis [AGEP] in English medical literature)

to rename the condition formerly termed exanthematic pustular psoriasis

by Baker and Ryan in 1968 [2], to describe

a subgroup of patients with pustular psoriasis who had a very acute pustular

eruption, drug intake and no history of psoriasis.

Fenofibrate is a lipid regulating agent of the fibrate class approved

as an adjunct to diet in the treatment of adult patients with primary hypercholesterolemia,

mixed dyslipidemia and hypertriglyceridemia [3,4,5].

Recent data also indicate its utility for optimizing reduction in the risk

of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes and metabolic

syndrome, as well as delaying the progression of diabetes-related microvascular

complications, when combined with a statin [4].

Cutaneous adverse reactions (CAR) attributed to fenofibrate are rare and

include acute hypersensitivity reactions such as severe skin rashes, urticaria,

photosensitivity reactions, contact dermatitis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome,

toxic epidermal necrolysis, pruritus, alopecia, herpes zoster, herpes simplex,

acne, sweating, nail disorder and skin ulcer [3,5,6].

AGEP had never been associated with fenofibrate therapy.

Case Report

A 68-year-old woman with atrial fibrillation, arterial hypertension and

diabetes mellitus was taking acenocoumarol (dose based on International

Normalized Ratio (INR) values), digoxin 0.2 mg/day, amlodipine 5 mg/day

and rosiglitazone/metformin 2 mg/1000 mg once/day for several years. Three

weeks before admission the patient was diagnosed with hypertrigliceridemia

and was prescribed fenofibrate 267 mg/day. After 7 days of treatment, she

developed an erythematous pustular eruption on inframammary folds, axillae,

inner surface of both arms and laterothoracic areas associated with subfebrile

temperatures. She attended her local doctor and was suspected to have scarlet

fever, being medicated with intramuscular penicillin. Because no clinical

improvement was achieved and the rash continued to spread, she returned

to her doctor 2 days later and was advised to cease penicillin, was medicated

with intravenous bolus of corticosteroid for suspicion of drug-induced cutaneous

reaction, and was referred for a dermatological opinion concerning diagnosis

and treatment.

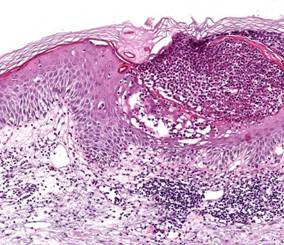

On physical examination, we observed widespread edematous erythema over

the trunk, arms, buttocks, thighs and intertriginous areas, accompanied

by many small, nonfollicular, superficial pustules. On the neck, axillae

and inframammary folds confluence of pustules produced lakes of pus

(Fig. 1). The mucous membranes, palms, and soles were unaffected.

She was febrile (38.2

oC) and referred malaise and asthenia. She denied previous

therapy with fenofibrate and reported no adverse reaction to other drugs.

Personal or family history for psoriasis was negative.

| Fig 1: Typical appearance of acute generalized

exanthematous pustulosis in our patient: disseminated

small non-follicular pustules on erythematous and edematous

skin. In some areas, confluence of pustules produced

lakes of pus (close-up). |

|

Routine blood tests revealed leukocytosis (12400/mm3; normal:

4000-11000/mm3) with neutrophilia (10400/mm3; normal:

2500-7500/mm3) and raised C-reactive protein (16.6 mg/L; normal

< 5.0 mg/L). The remaining blood panel, urinalysis and cultures obtained

from blood samples and pustular swabs were normal or negative.

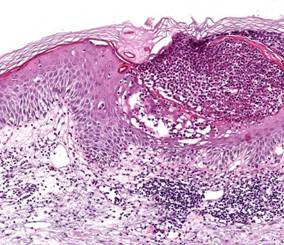

The skin biopsy specimen demonstrated non-follicular intra- and subcorneal

pustules containing neutrophils, spongiosis, mild edema of the papillary

dermis and perivascular inflammatory infiltrate mainly composed of neutrophils

and eosinophils (Fig. 2). The histological findings were consistent

with the clinical diagnosis of AGEP.

| Fig 2:

Histopathological

examination

showing subcorneal pustule with neutrophils and spongiosis

(H&E stain, 40x). |

|

Management involved withdrawal of fenofibrate, introduction of oral prednisolone

(30 mg/day with a 2-weeks tapering), bathing with antiseptic solution (potassium

permanganate) and emollients, which resulted in resolution of the exanthema

within 1 week, followed by thin desquamation. For lipid control, the patient

was prescribed simvastatin 20 mg/day.

About 2 months after the resolution of the dermatosis, skin patch tests

were performed with the Portuguese Contact Dermatitis Group standard series

and fenofibrate capsules (267 mg) at 1, 5 and 10% in petrolatum. The tests

were read at 48 and 96h and scored according to the International Contact

Dermatitis Research Group grading scale. Only positivity for potassium dichromate

(+) was detected. After a 6-month follow-up period there was no recurrence

of the skin lesions.

Discussion

The estimated incidence of AGEP is approximately 1 to 5 cases per million

per year [7,9].

More than 90% of cases of AGEP are drug induced, particularly by antibiotics

and mainly beta-lactams and macrolids [7,8].

Few cases are related to other causative factors such as viral infections,

mercurial antiseptics, topical agents, pneumococcal vaccine, herbal medications,

foods, ultraviolet light exposure and spider bite [7,8].

Bernard et al. [9] demonstrated a high frequency

of HLA-B51, -DR11 and -DQ3 in patients with AGEP. The interval between the

administration of the drug and the onset of the eruption is usually 2 or

3 days for antibiotics and longer (3-18 days) for drugs other than antibiotics.

Our patient started fenofibrate 7 days before the eruption.

The diagnostic criteria of AGEP, initially proposed by Roujeau et al.[8]

include: (i) numerous, small, non-follicular and sterile pustules arising

on a widespread edematous erythema, with burning and/or itching; (ii) fever

exceeding

38oC; (iii) histopathologic findings of subcorneal and,

sometimes intraepithelial spongiform pustules; (iv) blood neutrophil count

above 7000/mm3; and (v) acute course with spontaneous resolution

of the pustular eruption in less than 15 days, followed by a characteristic

postpustular pin-point desquamation. Recently, a validation score based

on morphologic and histologic criteria, and disease course was elaborated

by the EuroSCAR study group [7]. Our patient

had a classic drug-induced AGEP with typical morphology, course and histology,

fulfilling the diagnostic criteria established by Roujeau et al. [8].

Besides, according to the criteria of the EuroSCAR study group, fenofibrate-induced

AGEP was considered a definite diagnosis (12 points; range for definite

AGEP, 8-12).

Lymphocyte transformation tests and skin patch tests (SPT) can be useful

for diagnostic confirmation, and positive results suggest involvement of

T cells in AGEP [10]. The percentage of

positive SPT to the culprit drugs is frequently high (up to 80%) in patients

with AGEP, particularly for antibiotics [11].

However, negative tests do not exclude this diagnosis.

Early diagnosis of AGEP and the differentiation from other dermatoses,

such as generalized pustular psoriasis (von Zumbusch type), subcorneal pustular

dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease), hypersensitivity syndrome with pustulation,

pustular vasculitis or even toxic epidermal necrolysis [7,8],

are important to avoid unnecessary and potentially dangerous drug therapy.

Additionally, as occurred in our patient, the combination of fever, leucocytosis

and pustules is often misdiagnosed as acute infectious disease leading to

unnecessary administration of antibiotics.

The withdrawal of the responsible drug is the main treatment for AGEP,

in combination with topical corticosteroids and antipyretics [1,7].

Because lipid lowering is effective for primary and secondary prevention

of cardiac events, one might expect an increase in the use of the various

lipid-lowering agents including fenofibrate and, as a result, the associated

CAR.

To our best knowledge there are no previous reports in the international

medical literature of AGEP induced by the ingestion of fenofibrate. Therefore,

this drug should be added to the list of potential causes of AGEP.

References

1.

Beylot C, Bioulac P, Doutre MS. Pustuloses exanthématiques aiguës généralisées,

à propos de 4 cas. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1980; 107: 37- 48.

PMID: 6989310

2.

Baker H, Ryan TJ. Generalized pustular psoriasis: A clinical and epidemiological

study of 104 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1968; 80: 771- 793.

PMID: 4236712

3.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Drugs@FDA: Fenofibrate. Available at:

http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm. Accessed

August 10, 2008.

4.

Zambon A, Cusi K. The role of fenofibrate in clinical practice. Diab Vasc

Dis Res. 2007; 4 Suppl 3: S15- 20.

PMID: 17935056

5.

Balfour JA, McTavish D, Heel RC. Fenofibrate: A review of its pharmacodynamic

and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in dyslipidaemia. Drugs.

1990; 40(2): 260- 290.

PMID: 2226216

6.

Roberts WC. Safety of fenofibrate: US and worldwide experience. Cardiology.

1989; 76(3): 169- 179.

PMID: 2673510

7.

Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Bavinck JNB, Vaillant L, Roujeau J-C. Acute generalized

exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol.

2001; 28: 113- 119.

PMID: 11168761

8.

Roujeau JC, Bioulac-Sage P, Bourseau C et al. Acute generalized exanthematous

pustulosis: Analysis of 63 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1991; 127(9): 1333- 1338.

PMID: 1832534

9.

Bernard P, Lizeaux-Parneix V, Miossec V et al. HLA et predisposition génétique

dans les pustulosis exanthématiques (PEAG) et les exánthemes maculo-papuleux

(EMP). Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1995; 122: S38.

10.

Britschgi M, Pichler W. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a clue

to neutrophil-mediated inflammatory processes orchestrated by T cells. Curr

Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002; 2(4): 325- 331.

PMID: 12130947

11.

Wolkenstein P, Chosidow O, Flechet ML et al. Patch testing in severe cutaneous

adverse drug reactions, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal

necrolysis. Contact Dermatitis. 1996; 35: 234- 236.

PMID: 8957644© 2008 Egyptian Dermatology

Online Journal

|